Danny and I had a difficult friendship. I’m not sure most of the time we even were friends. We were in the same form and the same sets. We spent a lot of time together. He was one of those kids who was always there, and he probably thought the same about me.

Danny never combed his hair, or it would appear washed it, and his protruding teeth were not always clean. He was gloomy at times. He talked about the end of the world. Oddly, he kept a spider in a matchbox. He was small and scuttled about, his head down. His physiognomy and manner earned him the gangster-style moniker of Danny Rat. Kids can be cruel.

Danny and I had a fight in the changing rooms before PE. It was over something stupid, and we suddenly found ourselves going full Lord of the Flies, punching each other wildly, while the other boys savagely bayed for blood. There was a moment when the human side of my brain said, ‘What are you doing? This isn’t you!’ The ape side cackled – ‘Make him bleeeeed.’

The mob got their blood. Danny, who did taekwondo, had the perfect guard and, from nowhere, punched me twice in the nose. Like a boxer with high cheekbones, it was my weakness. Not that it was ever that hard to cause my nose to bleed. Blowing it and even sniffing in dry weather has the same effect. The fight was stopped, and I was taken away to be patched up. Danny was deemed the winner. He drew blood. It was not something I ever wanted to do again.

Things changed in the sixth form, and we started getting on better. Danny was taking more care of his personal appearance. He grew his hair and kept it washed. He looked like he was modelling himself on Dave Grohl, who had just released Foo Fighters’ debut album.

Danny did two important things for me, which I’m grateful for. Firstly, he introduced me to alternative music. He lent me a compilation CD that included Radiohead. It was the first time I heard Creep, and like many other teenage boys at the time, I instantly related to it. I imagine Danny felt that way, too.

Secondly, most importantly, he invited me to go to Rock City with him, with a few others. A bidding that changed my life.

Life before Rock City involved going out in Hucknall every Friday night. My whole sixth form did. We were mostly underage, and this wasn’t something the pubs and bars seemed to care about. They were raking it in. Unless the cops felt arsed to do a patrol, the bar staff hardly ever requested to see our NUS ID cards, with, of course, doctored date of birth details.

Hucknall had no nightclubs. What it did have was The Byron. The pub had an upstairs room half the size of a tennis court, where a DJ played the latest Euro cheese dance music and remixed chart hits. For some reason, it was the place everyone wanted to be. You would have to queue for ages to get in, and there was no guarantee you would. The bouncers were strict. You weren’t always told why they weren’t letting you in. If you did, it was deemed an achievement. I remember celebrating at the top of the stairs whenever I did. That was the good bit, being chosen. Getting what you want is another story. Too loud. Too packed. Too many pricks. The lager, expensive and pissy. You couldn’t talk to anyone because you’d just be shouting and spitting in their ear. I spent some of the time in my own head, the words to Creep and How Soon is Now, on repeat, while watching my school friends having a great time, laughing, dancing, flirting, kissing… maybe something else later.

What the hell am I doing here?

I tried nightclubs in Nottingham. The music wasn’t right. I hated the dress code – shirt, trousers, shoes. Anything reminding you of school surely should be avoided. You had to pay for the pleasure back then too. I enjoyed being with friends, getting drunk and farting around, but I spent most of the time hypervigilant. I worried about spilling someone’s pint and getting glassed in return. I witnessed violence inside and out. Bouncers pressing heads against the pavement until the police arrived.

They were often sleazy places. I would watch from the side, or balcony, as men prowled, creeping up to women on the dance floor. Grabbing and then gyrating themselves, uninvited, against an unsuspecting victim. Was this something that was ever encouraged? I’d seen women get off with men just so they left them alone.

I don’t belong here.

‘Come with us to Rock City,’ said Danny.

Mum had warned me about Rock City. It was full of Hell’s Angels, apparently. She made it sound rough and unsafe. I wasn’t sure it was right for me. I imagined long haired oily rockers with big beards who would delight in humiliating me by putting me in a headlock. I don’t know why. I think I’d watched too many old Clint Eastwood films, the ones with the orangutan who liked sticking his middle finger up at people.

‘It’s nothing like that,’ said Danny, laughing. ‘It’s student night.’

‘And, no dress code?’

‘Wear what you want.’

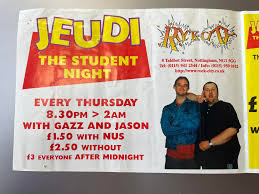

The student night was named Jeudi and was on every week from 8.30pm to 2.30am.

I laid out my jeans, random band t-shirt, and cheesecloth shirt (to be tied around the waist due to inevitable temperature increase as the night wore on). My blue Adidas Gazelles waited by the door.

It’s hard to explain the first time, but you know when it’s significant. You know you’ll remember the moment forever – like your first day at school, or seeing your football team for the first time. At Rock City it was when I walked the stairs from the lobby, and opened the double doors to hear music I loved, sounding better than ever.

There was black everywhere. The walls, the ceiling, the furniture, the bars, the lino, apart from the wooden sticky dance floor. (I made the mistake once of wearing white jeans and I woke up the next day to see them covered in black streaks like a miniature car had driven over them).

A Rock City mural on the back wall of the stage, made with different tones of glow-in-the-dark-paint, had a thousand different names scratched into it.

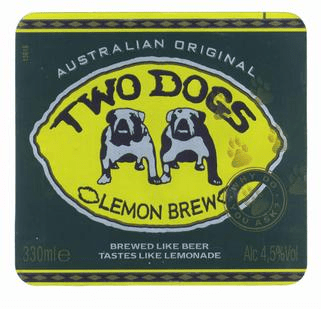

As innocent as I was, and after what Mum told me about Rock City, I couldn’t help thinking it was all a bit illicit. Something shouldn’t be this much fun. Should I even be here? This was highlighted when someone offered me a sip of their can of Two Dogs. Not an E, or anything illegal like that, but alcoholic lemonade. I hesitated. I thought he’d smuggled It in. Alcoholic pop? Alcopop. Oh, you can buy it here? Wow.

‘You’ll never pull a girl at Rock City,’ Danny told me as we sipped from cans of Red Stripe. We were chatting, enjoying the music, watching people dance, and building up the courage to join them.

Some girls had the Mod look, others modelled themselves on Louise Wener from Sleeper. Some had an androgyny similar to Justine Frischmann, the lead singer of Elastica. They mostly wore tees, jeans and trainers. No-one was bothering them which was great to see. I never saw any trouble. ‘Safe space’ wasn’t a thing in the 1990s, but if it was, Rock City was for us all.

Danny wasn’t being mean. It was just his experience. This wasn’t the main reason for going, and it wasn’t like he or the others had much luck anywhere else. I was, however, desperate to meet girls, like those on the dancefloor – girls who didn’t know me. Who didn’t know my character or the reputation I had. Nice, funny, smart, but just a friend… I could start afresh. It never felt like I could be with any girl in my sixth form. Many of them were already in relationships, but also, why would I? I couldn’t think of anything more awkward. The biggest reason of all, perhaps, was that none of them appeared to be into what I liked, and that mattered.

At Rock City, I felt I could be myself. I felt safe. I felt I was among people who cared about what I loved. Feeling that I wouldn’t be mocked for wanting to dance like a twat to Blur’s Sunday Sunday, or Black Grape’s In the Name of the Father, was liberating.

The knock-on effect of feeling free and having fun, was that it was actually quite attractive. I suddenly found I was getting attention and despite what Danny said, it turned out you could pull a girl at Rock City. In my case, every week (until I got a girlfriend). Maybe they pulled me. This sounds like a massive brag. Hear me out. When you’re in a safe environment, when you love the place, when you feel free to dance, sing and twat about, with a big smile on your face… Well, funnily enough you’re much more fanciable than if you’re standing at the side looking like the world is on your shoulders and wondering why no-one wants to snog you (I refer you to the bit about The Byron).

I recall catching the eye of a pretty redhead, as we sang along to Pulp on the dancefloor. We met at the bar and I bought her a JD and coke. We sat down. We talked. We kissed. She finished her drink, said thanks and walked off. I’d been used, but hey ho. I chuckled to myself.

The Thursday night Rock City routine, along with the gigs I went to, continued until I went to university in summer 1997. I didn’t visit again until the following year, and sadly, it had all changed. I went during Freshers week before I was due to return to my uni. It was all wrong. There was an Ali G impersonator on stage. I was never a big fan of the character, but an impersonator? Nah. The DJ played hits by the boy band Five and Robbie Williams. It was crushing. I left early.

I’m a late GenXer, born in 1978, so perhaps this new crowd were the first Millennials to experience Rock City. A fresh crowd, new tastes, music and fashion. It had changed in a short space of time. I felt sad, but nothing lasts forever. Who’s to say what I experienced in those two years wasn’t to the expectations of others previous to me?

I have plenty of contentment in my middle age, but whenever I go back to Rock City I feel homesick for those times in my teens – a version of myself that’s long gone. Gleeful, carefree and happy.

Thanks for the invite, Danny. Wherever you are.