As a kid I would get mardy about football. I would be called mardy. I would be told not to get so mardy. When I was upset or/and crying, invariably I’d be told I was just being mardy or ‘having a mard on’. But being accused of being mardy would only make me more mardy and thus send me into a spiral of mardiness that lasted forever. (For those in the south, and for anyone who has never heard of the Arctic Monkeys, mardy is a Northern/East Midlands word meaning sulky or grumpy).

noun. Neil was told he was being mardy after he threw his slipper at the wall after Forest conceded a second goal against the run of play.

adjective. Neil was told he could ‘get all mardy about it’ but it wouldn’t change the fact that Forest lost 5-0.

I say ‘as a kid’ I would get mardy. I still am that kid. I never grew out of it. The simple, and obvious, reason is that I have the same brain. But my mardiness is likely a consequence of my neurodivergence. I can’t help being oversensitive and getting overly upset about a game and a football team, plus a myriad of other things in this life.

Two affecting football matches took place within the space of 12 months that I still return to even now after 35 years. In July 1990, England lost the World Cup semi-final to West Germany, with my idol Stuart Pearce having his penalty saved in the shootout. The following May, Forest lose to Spurs in the FA Cup final. Football, and particularly my hometown club Nottingham Forest, had taken its grip before these matches, but the emotional reaction was strong, and some might say over the top, in both.

Firstly, what’s the appeal of football to a neurodivergent brain? Why did I ever get involved, and why, despite my best efforts to abandon it, have I stuck with it?

People with ADHD have lower overall dopamine levels compared to those with neurotypical brains. It means we have to get our kicks from somewhere else to maintain focus and motivation, and more importantly to feel happy. Watching football, and feeling part of a football club’s community, is great for dopamine due to the excitement that a goal, a win, a modicum of success, can bring. A goal can trigger the release of dopamine, boosting mood and happiness in the brain’s reward system. Winning is a powerful feel-good experience. I’ve never taken a drug like ecstasy, but I imagine it’s a similar feeling – you’re in love with everyone and everything. Nothing can stop you. It’s worth noting here that many ADHDers have addiction problems due to the quest for dopamine. And, perhaps that’s my problem with football.

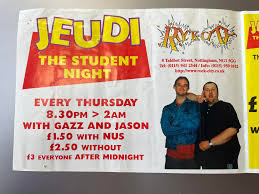

The connection with others, complete strangers, celebrating success, also floods the brain with dopamine. I’ve built strong relationships and friendships due to Forest (another reason I’ll never escape it) but it’s also soothing being able to share the same experiences, good or bad. Plus, nothing beats the feeling when I’m away from Nottingham, perhaps abroad, and I hear a stranger say, ‘You Reds!’ after spotting a badge somewhere on me. It denotes friendship, a shared love, and validation for the choice of your club.

The opposite of all this during the good times is what happens when your team loses or goes through a bad patch. Negative feelings lead to the release of stress hormones like cortisol. However, the drive for stimulation and dopamine keeps you going and if anything, the stress makes the highs really fucking high.

Because of the connection I will often say we played well rather than they played well, or, we got spanked, and not they got spanked, which can be problematic for a neurodivergent brain. I take a Forest defeat personally. I shouldn’t, but I do.

I’ve defended Forest so hard over the years when at times they’ve scarcely deserved it. It’s because it feels like I’m defending myself. Therefore a negative comment from a pundit, a rival, a friend who supports another team, can cut deep. They’re hurting me, not mocking the team’s performance. I know I should keep the two distinct.

ADHDers have a heightened sensitivity to criticism, which is linked to Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD), leading to intense emotional pain at times. This sounds dramatic and while I joke about mardiness, I’ve learned that RSD is the reason I’ve struggled with my emotions throughout my life.

When the final whistle went in the 1991 cup final, I was devastated, and what followed was an hour of wild unregulated emotion. I was hysterical. I reacted angrily. I tried to hide the tears from my parents, and a friend who had come to watch the game, behind the arm of my chair, and a cushion. After collecting the cup and their medals, the Spurs players walked down from the Royal Box and in turn celebrated into the barrel of the camera, directly at me. (The one who sticks in my memory is Justin Edinburgh, who had been successfully winding Roy Keane up all game).

They were deriding me, their behavior demonstrated that I was a loser. They, and the result, confirmed all the negative self-beliefs I had about myself, and I reacted by swearing at the TV, sticking my fingers up at them, telling them to ‘fuck off’, in a tearful rage. In that moment, due to the RSD, the inability to not react to the perceived criticism and failings was impossible. I’ve beaten myself up for years for reacting like I did, but now I know I couldn’t help it.

There’s also the small matter of injustice about the match, something else which led to my initial reaction and had me ruminating in the weeks and months that followed.

Paul Gascoigne committed two wild brutal fouls on Gary Charles and Garry Parker, which in any other game, and if he was any other player, would have resulted in Spurs going down to 10 men. Gazza eventually left the pitch but on a stretcher – an injury sustained during one of the fouls. He was treated like a gallant hero, when he should have been the villain. Before he ‘bravely’ left the game, the resulting freekick, from one of his fouls, was dispatched into the top corner by Stuart Pearce. Justice served. A goal that deserved to win any cup final. Forest led 1-0 at half-time. Our goalkeeper Mark Crossley also saved a penalty from Gary Lineker. Everything was going right. However, the player who came on Gazza, Paul Stewart, had the best 45 minutes of his life, scoring the equaliser. The game went to extra-time and Forest defender Des Walker scored an own goal (further perceived humiliation) to hand Spurs the cup. It shouldn’t have been this way.

ADHDers suffer from ‘justice sensitivity’. We react quite intensely to unfairness while experiencing strong emotions like anger. We also have difficulty letting things go. There’s a strong need to restore justice. This manifests itself in all walks of life from politics to people not picking up their dog’s shit. Justice sensitivity explains my reaction to the 1991 cup final and why it still bothers me from time to time.

I’m now in my late forties. I still get upset, but I regulate my emotions better through a variety of methods – journaling, mindfulness, and good old fashioned talking (something I wouldn’t have done at 13). I can let things go during a match, but sometimes there’s a perfect storm that sends me into a spiral of negativity – thus flaring up my ADHD symptoms.

It’s Forest vs Bournemouth, 23 December 2023. The referee is Rob Jones, who with breathtaking incompetence sends off our defender Willy Boly after 23 minutes. Even at the distance I was sat, 70 metres away, I could see that Boly had won the ball. I even remember excitedly exclaiming ‘great tackle!’, only to see the inept Jones give Boly his second yellow. Replays will show not only did Boly win the ball, he was also fouled in the process – a possible red for the other player. Forest also had a penalty controversially turned down when the ball struck an outstretched arm. Despite the injustice we went a goal up. But then they scored twice in seven minutes. We equalised, only to lose the game late on.

I was so close to the Bournemouth fans I could see their gleeful, smug faces. The derision was all aimed at me. Like in ‘91, I was the loser. I was the one being mocked. Even the neurotypical Forest fans that day would have struggled following what happened. I don’t think I uttered a word to anyone until late in the evening. The justice sensitivity, the RSD, the struggle to control my emotions, the inability to snap out of it, all combined to make me feel terrible. I kept all these feelings inside when perhaps crying and raging would have been more therapeutic. However, displays of emotion as an adult are deemed inappropriate and unacceptable. Man the fuck up, etc etc…

How can I, or someone else with ADHD, or not, have a better experience?

- Create distance and separate the football team from who you are. While supporters play their part we don’t make the decisions on the pitch. Not even the best teams win all the time. That would be boring. You need the bad times to feel the good times.

- When people are taking the piss, they’re aiming it at the team, not you personally. You are not being criticised or attacked. Feel free to laugh it off. If they are attacking you personally then they’re not friends, and if you wouldn’t let them into your house, don’t let them into your head.

- Be more objective than tribal. You can question players, coaches and the hierarchy. You’re not being paid to defend them.

- Acceptance. No matter what happens you’ll always support the club and find some joy in that. Joy doesn’t always come from winning. It comes from the connections you make through supporting the club. Do not rely on the football team for your happiness.

- We don’t control what happens when things go wrong. No amount of anxiety will change what happens. We can only control how we think about something.

- Acknowledge that human beings, especially Rob Jones make mistakes (time and time again). He can’t help being incompetent. It’s something he has to live with. Feel good in the fact that when you wake up in the morning you’re not Rob Jones.

- Finally, as ever, if the plight of a football club or the result of a match, is the only thing causing you anxiety then you don’t have anything serious to worry about in the present.